Catching up and lessons learned

Seems like longer, but just a year ago, in the run up to the fall 2020 semester, the plan for Mon County schools was “hybrid” attendance. Students with last names beginning A through L would attend in person two days a week, with M through Z attending remotely, online. They would switch places two other days, and on the fifth day everyone would be remote.

Best laid plans. What really happened is, students started the semester fully remote because of a spike in COVID-19 cases, and they didn’t go hybrid until October. Thanksgiving sent them back home until nearly February. After one more month of hybrid attendance, enough school personnel had been vaccinated that families were able to choose between fully in-person and fully remote for the remainder of the school year.

But that oversimplifies what felt, week to week, like swirling chaos.

“The word we used was ‘pivot,’” says Clay-Battelle Middle / High School Principal David Cottrell. “And it was almost a constant pivot. We’d just get something planned, and then we’d have to change because somebody had been through contact tracing or there was some new rule. It was just constant change.”

Teachers rewrote lesson plans and found their internet chops. Students juggled multiple online learning platforms and disruption to their friendships. And parents held it all together somehow on top of the COVID-19 stresses to their own careers, incomes, and family and social lives.

Looking back, though, most people already feel that everyone made the best of a tough situation. It didn’t all work. But then, a lot of it did—well enough that some things will become standard practice.

We talked with families and educators across the county and with Schools Superintendent Eddie Campbell about how last year went, what has families concerned, and which things changed for the better. Here’s what it all means for school this fall.

Smoothing Re-entry

Practically since the pandemic started, we’ve all been saying we just want to get back to normal. At the time of this story’s posting, the plan this fall is for students to ride buses together and be in the classrooms with their teachers, mask-free, just like normal. Principals talk about the fall semester as a return to what we’ve known—with extra emphasis on the feel-good.

“Everyone’s getting to come back to what they recognize as ‘school’—and the events that are traditional and important will happen again,” says Ridgedale Elementary Principal Sheri Petitte.

“We’re going to make it a normal school year—using lockers again, switching classes like we normally do,” Cottrell says of Clay-Battelle. “And there has to be time for the fun stuff—like student council elections. We have to have a homecoming. We have to have athletics.”

Still, as much as everyone craves normalcy, it’s going to be an adjustment, Mon County Schools Superintendent Eddie Campbell says. “That’s just a fact.”

That’s based, in part, on the numbers. When families had the choice of sending students back into the classroom in March, around 70 percent went back countywide—more in the elementary grades, fewer at the more independent middle and high school levels. That means about 30 percent finished the year as remote learners. A lot of them haven’t seen the inside of a school for 17 months. Even the ones who did finish last year out in person haven’t experienced the full hurlyburly again yet.

It’s also based on the experience with the students who did return in March. After a year on their own, some struggled. “When you are at home, you can eat when you want, go to the bathroom without getting permission to leave the room, work at your own pace,” Petitte observes, reflecting on her students’ return to Ridgedale. Many just found it tiring. “Socially, it can be overwhelming to join a group of 25 when you are used to being a class of one.”

So, countywide, teachers and staff are going in with the expectation that “normal” is going to be a little weird for a while, and that some students will be challenged by all the structure and stimulation. “We’ve done a lot of work this year, both with our administrators and our teachers, in preparation for this,” Superintendent Campbell says. “We’ve been preparing our staff for it with professional development around the idea of social and emotional learning.” Social and emotional learning guides students toward self-awareness, empathy, and other tools for personal resilience and social harmony.

The school system is also adding counselors. Every school will have a minimum of two school counselors this fall, Campbell says.

Bridging gaps

Teaching online last year, teachers literally had windows into their students’ home environments.

It reminded Cheat Lake Elementary second grade teacher Debbie Wise of the home visits elementary teachers started school years off with in Pittsburgh, earlier in her career. “That told you so much about a student,” Wise says. “From that, you know if Susie comes to school and she’s not feeling well, that’s probably because where they live they’re not getting breakfast or Daddy is very loud or Mommy is not in the picture. Those things shape those children. It’s not a cookie-cutter classroom—knowing those things has a lot to do with how you teach them.”

The pandemic aggravated those kinds of family stressors, and teachers across the county say last year’s live online interactions helped them know when a student needed extra support or flexibility.

Monongalia County also started the COVID school year with its largest-ever team of outreach facilitators—social workers by training, hired into positions the system has increased from three in 2018 to six last year and nine in the fall of 2020.

“Their big role is eliminating the barriers that are in the way of students being successful in school,” says Michael Ryan, coordinator of student supports for Monongalia County Schools.

Outreach facilitators made sure families had the information their kids needed to log in for remote learning and helped them find a school-provided internet connection if they didn’t have internet at home. When a student would stop engaging and no one at home answered a teacher’s emails or phone calls, outreach facilitators stepped in. “They could find families that no one else could find, because they’ve built those relationships,” Ryan says.

They solved much harder problems, too. “They worked hours before and after their work days, delivering food, setting families up with resources,” Ryan says. They connected families with counseling, food pantries, and the free store and emergency financial assistance at Christian Help. In at least one instance, they got a struggling family into stable housing.

“That is money well spent,” Clay-Battelle Principal David Cottrell says of the outreach facilitator program. Ryan agrees. “I think last school year really highlighted what the outreach facilitators can do for our school system and how vital and important they are.”

Every Mon County school has at least a part-time outreach facilitator. This fall, the addition of one more makes 10 countywide.

CAtching Kids Up

It became clear in December, a few months into the 2020–21 school year, that the remote-then-hybrid-then-remote-again regime had lost some kids along the way. “When you see traditionally good students falling by the wayside, that sets off red flags,” Campbell says. “The teachers needed to re-engage these kids—reach out to them and their families, in multiple ways if necessary, figure out why they weren’t logging in and turning in assignments, and find ways to make those things work.”

The redoubled individual efforts teachers made re-engaged a lot of students and set a better tone for the rest of the school year, he says. In part because of that, the year-end results are probably better than our worst fears.

“When we were going back into the classroom, in March, I was thinking it was really going to be bad,” says Cheat Lake Elementary second grade teacher Debbie Wise. “Surprisingly, the iReady scores”—that’s an online instruction and assessment tool for reading and math—“showed our kids were just where they’re supposed to be. Of course, some were low, but it was wonderful to see that they did not fall behind that much.”

Still, the biggest questions on many people’s minds are, how much less did students progress than in a normal year, and how is the school system going to catch them up?

There’s no hard data yet on student achievement. The district is looking at the results of state-mandated end-of-year testing, Campbell says, and it’s working with a national research firm to get a clearer picture of the year’s academic growth. “We definitely know that the growth rates were not as fast, didn’t move as far as what they typically would outside of a pandemic,” he acknowledges.

But the district’s response, he says, isn’t remediation—holding students back, making them retake classes or do grades over. It’s accelerated learning: direct assistance where assistance is needed.

Like some COVID-19 vaccines, the accelerated learning comes in two parts. The first part already took place as Summer Avalanche, a supercharged version of the district’s usual July Summer Snowflake enrichment program. It offered 350 sessions at the county’s 19 public preK–12 schools, up from 100 in a normal year, for a 9 a.m.–2 p.m. day instead of mornings only. There was a focus on language arts and math, but the learning was delivered as all kinds of fun. “This is not putting worksheets in front of kids to try to get them caught up,” Campbell explained before it started. “It’s math in yoga, math in cooking—variety, to get them engaged.” Many more teachers than usual offered sessions. And everyone worked back in the spring to make sure the families of the students who could benefit most understood that, this year, transportation and meals would also be provided. Compared with 1,000 students registered in 2019, “we got about 2,000 students signed up for four weeks,” Campbell says, “and that’s going to help them move forward before we even walk in the door in August.”

The school system is prepared to follow that up in the fall with a powered-up tutoring program. “We’re employing more interventionists,” Campbell says, “so we’ll have the ability to work with students one-on-one and in small groups, during the school day and after school. We’re going to teach at grade level—if they were a third grader last year, we’re going to put fourth grade material in front of them, and our tutoring programs will accelerate their learning as opposed to doing remediation.”

the internet is here to stay

Schools are, by nature, institutions of stability and repetition. At the same time, every school year is a whirlwind. Maybe because of all that, schools have been among the last environments permeated by newfangled digital technologies.

What a difference a pandemic makes.

Mon County Schools was better prepared than many districts for a surprise school year on the internet. Students in most grades were assigned Chromebooks several years ago, leaving only the lowest grades to be supplied in fall 2020.

And for the previous three summers, the district had offered a technology professional development camp for teachers—although the new skills hadn’t all made their way into classrooms.

“It’s difficult. I’ve experienced this myself as an educator,” Campbell says. “You have professional development activities, and you get excited about it and want to try it in the classroom, and sometimes the practicality isn’t there and the learning goes by the wayside.” But last year, he says, teachers were forced to put new resources and software platforms into practice.

It was a lot to take on all at once. Morgantown High School visual arts teacher Sam Brunett is thoughtful on the topic. “Teachers had to remain what they already were, which was classroom teachers, while also becoming their own little multimedia production studios.”

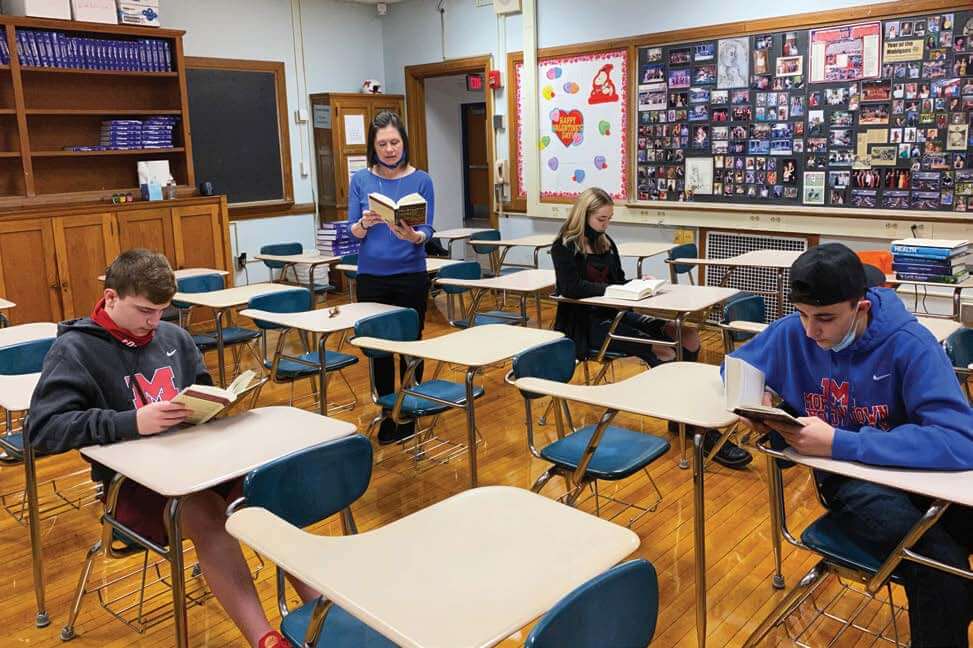

As an art teacher, Brunett does a lot of demonstration. “So I would teach at my desk, which I usually don’t do, with a document camera.” These mounted cameras that point straight down to capture a document or activity on a work surface, like the old overhead projectors, were the go-to tool during COVID. “So I was able to livestream for the kids at home, and a big-screen TV set showed it to the kids in the classroom. Then, if you can imagine teaching kids who are raising their hands and other kids who are writing you questions online at the same time you’re answering questions in the classroom—it became juggling.”

Trial and error took delightful turns. “I met with my homeroom for 20 minutes every morning, even when we were remote,” Brunett says. “There’s this thing I did for a while that was interesting. You can put up this blank white screen, and everybody has a chance to write something on that screen. I didn’t say anything. It took about five days for kids to see that they could draw. One girl, every homeroom, would do a drawing, and other kids would watch or comment. It was kind of a visual social experiment.”

More than one teacher told us they were scared, going into the school year, about teaching online, but soon realized they were able to do it. And a lot of them got creative. One augmented a civil rights unit with a civil rights–oriented “road trip” and had students listen to Motown songs online and write about the themes in the lyrics. Teachers took advantage of virtual tours of museums around the world. “It’s pretty nice to sit in your classroom in Blacksville, West Virginia, and do a virtual tour of the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.,” Principal Cottrell says. Music and theater teachers conducted practices online and orchestrated performances for classmates and families.

And a lot of them discovered improvements they’ll keep. Brunett found the document camera was a better way to demonstrate close drawing or sculpting than having 20 kids crowd around his desk. Some teachers mention liking their new confidence in looping a student in who has to miss school but could attend from home. And some recorded their lectures, so now anyone can review a missed class. “Because of the pandemic and having to reach out virtually, we discovered even more tools than we had in our vocabulary prior,” Brunett says.

School administrations came fully into the 21st century, too. Online forms, it turns out, are an easier way to get parental permissions and signatures. And with online meetings, no more need to schlep from home or work or other schools for meetings. “Face-to-face is always best, but virtual meetings are convenient for parents and staff when time is limited,” says Principal Petitte. “It’s a more productive day for everyone.”

Cottrell believes more confident and creative uses of digital technologies are in schools to stay. “Now that people have learned to do it, I think they like it,” he says. “And it makes sense. Ask anybody from practically 4 years old up about something, ‘Well, I’ll get on my phone and google it.’ That’s the way they learn anymore.”

students ran with tech, too

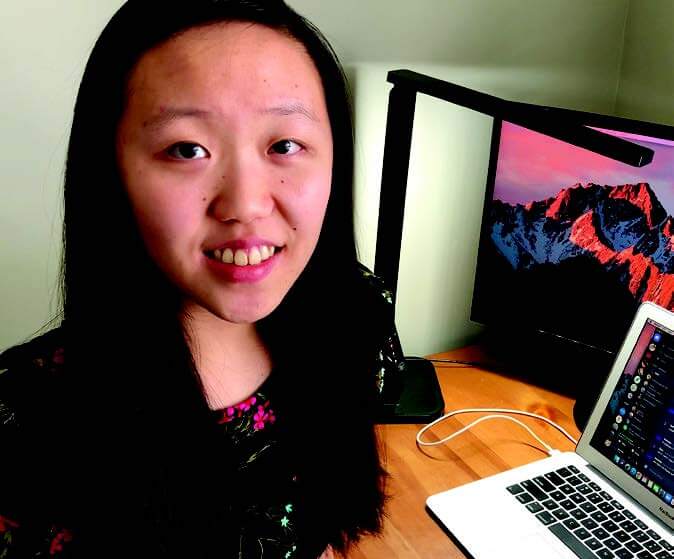

When COVID-19 shut schools down in March 2020, Lauren Shen was an 8th grader at Suncrest Middle School.

“I began to feel really isolated,” Shen recalls. So she initiated daily “study hall” meetings on Zoom with a few friends. “We bonded a lot, and we helped each other out if we had questions about how school was going. It just became a regular thing, to the end of that semester.”

In May, the usual Step-Up Day high school tour for rising 9th graders was just some online information. “We were kind of in the dark about how high school was going to go,” Shen says. “So I called one of my friends, she had just finished her sophomore year, to come to the study hall meeting. I moderated and asked her questions about high school—What is the schedule?

How do lunches work? How do you study for classes? It was a really valuable experience for us.”

So in the fall of 2020, Shen started a Discord server—that’s a user-friendly group chat, audio, and video app for building communities. She called it Students Connect, and she invited a wider circle, “people who are passionate about school, into extracurriculars, people I’d known in middle school. Some people invited their friends.”

A few days in advance of a meeting—most took place at 4 p.m. on Thursdays—Shen would send out a Zoom link with a topic. Early meetings revolved around remote learning and the transition to high school. Later meetings were sometimes study halls for common AP classes or, occasionally, a speaker invited from another club.

Around 30 people were participating in Students Connect when the spring semester ended, most of them 9th graders with a few older students and one rising freshman. Shen plans to continue the Students Connect Discord server in the fall, even if school is entirely in person and club meetings could happen in a classroom.

“I am really, really looking forward to going back to school and having that in-person experience again,” she says. “But we learned last year that things don’t have to be one-dimensional. I think that continuing this virtual aspect will give a lot more flexibility to the club, even if we do have in-person meetings. The main purpose is still to connect, whether it’s in person or online.”

The Biggest Need

And that highlights the main problem that was exposed by the necessity of teaching and learning online last year: Not everyone can get high-speed internet.

It’s definitely a problem in the western part of the county, Cottrell says. “I had kids who do not have internet access—or if they do, it’s not strong enough for them to watch a video or to do something else they might need for their class.” Most people have DSL internet through Frontier, he says. The maximum download speed of 18 Mbps falls far short of broadband. Monongalia County Schools sent buses out as Wi-Fi hotspots, and Cottrell says that helped. “But still, you’ve got the issue of kids having to get to those places to do that.” He himself, because his satellite internet service slows down or cuts out during storms, worked at the school last year, even when he was the only one in the building.

“I had kids who do not have internet access – or if they do, it’s not strong enough for them to watch a video or two do something else they might need for their class.”Cottrell

And it wasn’t just the western end of the county. Only 45 percent of households in Mon County use the internet at broadband speeds, according to Microsoft data published in March 2021 by The Verge. Families across the district, including in town, found their internet wasn’t enough when everyone was doing school and work from home.

“Even after the return to in-person learning, much of what we do outside of the classroom related to learning requires that our students have access to broadband,” Campbell says. “In education, we call it ‘the homework gap.’ There are a lot of activities that our teachers do with students—homework assignments may get posted through Schoology, for example. That’s why we have it. It’s our communication platform. And that’s preK through 12, across 12,000 students.”

It won’t be this school year, but relief may be in sight. In May, the Monongalia County Commission contracted with Ice Miller Whiteboard of Ohio to create a comprehensive broadband plan for the county. The plan is scheduled to be complete early next year. And thanks to $20 million in federal American Rescue Plan coronavirus recovery funds coming to the county, it may be possible to see the plan to fruition over the coming several years so our schools can take full advantage of the internet for the benefit of our students.

READ MORE ARTICLES FROM MORGANTOWN LOWDOWN

READ MORE ARTICLES FROM MORGANTOWN’S FALL 2021 ISSUE

Leave a Reply